Garrard in Swindon

The company that led a musical revolution

It is a name synonymous with the very best record turntables available during a lost vinyl age - and Swindon was its home for more than six decades.

Like the GWR, Garrard was a byword for quality and excellence, and its reputation was global. And, like the GWR again, just the mention of the name is still sufficient to generate a welling-up of pride among those who worked there, even if the industry it led has almost disappeared.

And there is a heart-warming twist in the tale to ensure that the affection for Garrard's continues.

Musical revolution

When rock 'n roll travelled across the Atlantic, driven by the American dream, the States hankered after Garrard's decks, and when the Beatles produced a musical revolution of their own, Britons - if they could afford it - preferred to listen to it on a Garrard.

The story begins right back in 1735 - long before the invention of the gramophone - when Garrard's began to make a name as producers of some of the world's finest jewellery.

Such was its reputation that by 1843, when Queen Victoria decided to create an official Crown Jeweller, it was Garrard's that was given the title - and it has kept it ever since.

It was not such a leap from precision jewellery such as watches to military range-finders - and because they had both the expertise and the capability, these were Garrard's main contribution to the First World War effort.

Post-war diversification

After the war the new arm of the company, which called itself The Garrard Engineering and Manufacturing Company, continued to diversify, this time moving into producing motors for gramophones and tools - and it was now time to move out of the rented Willesden laundry, North London, that was its makeshift factory.

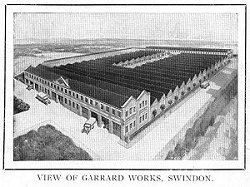

Its new home was to be Swindon.

It was headed by Major S.H. Garrard and a young engineer called Herbert Slade, who was about to play a major role in the development of Swindon and lead it into an era where dependency on the town's giant railway works would gradually decline.

If its workforce was a relatively meagre 30 when the factory opened in 1919, hopes were high, even against the backdrop of high unemployment caused by soldiers returning from the Western Front.

Already there was talk of the firm bringing 500 jobs, but if that sounded over-optimistic in such hard times, it turned out to be a gross under-estimate in the long-term.

Technological breakthrough

By 1925, eleven types of spring-driven motors were being made at a rate of 350,000 a year, and when Garrard's went public in 1926, further expansion followed.

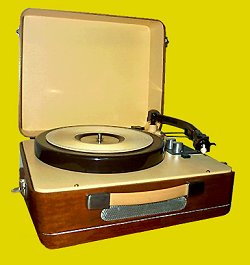

Then there was a technological breakthrough - the RC100, which could not only play a stack of 78s but even flip the records over to play the reverse.

But Garrard's expertise wasn't just applied to the household market.

Heavy duty, high quality turntables were required for recording and broadcasting from before the Second World War, and Garrard's many commercial customers included the BBC and several leading recording companies, for whom it produced tailor-made units.

These had various military applications, including the new technology of radar.

Fifties favourite

Herbert Slade cut all links with the jewellery business in 1945, and although he may not have foreseen that a golden age of records loomed, which could only be good for Garrard's and Swindon - he should be credited for the other ingredient in the firm's success story: exports.

The proportion of output that was exported - mostly to the United States - was 50 per cent and rising, and Herbert Slade received the CBE in 1950 in recognition of the firm's contribution to Britain's never-had-it-so-good economy.

Garrard's provided the rock 'n' roll era with its high quality turntables - and the Garrard 301 is considered 'an icon of design and performance' by hi-fi aficionados - but it also produced a range of lower quality models for the mass market. It was, indeed, a golden era, but it couldn't last.

Though Garrard's would continue to play a major role in Swindon for years to come, the late Fifties and early Sixties saw three events in quick succession which would completely transform its fortunes.

The beginning of the end

The first was the night of March 21, 1958 when the Newcastle Street factory was hit by a huge fire that, in terms of damage, was - and still is now - Swindon's worst ever fire.

Assembly lines for record changers, inspection areas and the despatch block were badly damaged or completely destroyed.

The answer was to temporarily move into premises belonging to Plessey, the electronics firm whose fortunes would become intertwined with Garrard's - and sooner than most could have predicted, as Plessey bought Garrard's in 1960.

Some said Garrard's never recovered from the 1958 fire, but more would probably argue that the firm's decline began with the 1960 sale to Plessey, which Herbert Slade refused to call a take-over, passing it off, instead, as 'a get-together'.

Herbert Slade

Although the family was still involved, hindsight tells us that with Herbert gone, Garrard's golden era was ending too, even if the momentum the company had built up meant that it was still a huge operation into the Seventies.

This is a good point to stop and take stock of how far the company had come - and how far it would soon fall.

From 27,000 square feet of factory space in 1919, it had now grown to about half a million square feet and had not one but three factories - at Newcastle Street, a converted aircraft factory at Blunsdon and another at Cheney Manor.

And profits were still running at £1.5million.

Japanese imports

Within five years, however, losses were running at £10million and the writing was on the wall as Garrard's failed to compete either economically or technologically in a new era of mass-produced, miniaturised hi-fi.

The final nail in the coffin was probably an attempt to 'go it alone' and bring Garrard's American sales agency (by now called the British Industries Corporation) back under closer control. It proved disastrous.

Mass redundancies were inevitable and two thirds of the workforce was wiped out in a single day in 1978 as the Blunsdon site was closed.

Final closure In 1979 Garrard's was sold to a Brazilian firm, Gradiente, for a nominal fee, and in 1982 production in Swindon ceased altogether - the last 179 jobs out of more than 4,500 less than ten years earlier, finally axed.

It was 'a tragedy' according to Mabel Slade, widow of Herbert, who said: "It was nothing when he started it and he built it up to be the pride of Swindon. Now it it nothing again".

Garrard's had played a significant role in the Swindon economy, especially in its development after both world wars, being one of the industries that alleviated the decline of the railway works, but it had also provided employment for a new type of worker during and after the war - women.

In the words of the local press, Garrard's had 'a long history of precision engineering and success which is a tribute to the ingenuity of Swindon management and craftsmen and the patient skill of the town's women who made it all possible.'

Still remembered in Swindon

Garrard's had also had a role to play in the wider community, thanks largely to the efforts of Herbert Slade who left his mark on amateur sport, for example, being President not only the Swindon and District Football League for many years but also Swindon Cricket Club.

Garrard's also had a sports ground to rival British Rail's in Swindon - now lost under part of the Greenbridge complex but commemorated in a road name, Garrard Way.

The plan was to repair and hand-make turntables to the same high standards for which Garrard's had become famous.

Trading from Lambourn, about half an hour's drive away, Garrard's has almost - but not quite - come 'home' to Swindon.

And Garrard's lives on in the Garrard 501 and 601 - models which echo the prestigious 301 and 401 of Garrard's golden era.

Handmade to order and shipped around the world, they provide a refreshing footnote to a major chapter in Swindon's rich industrial heritage.

Factfile and links:

Workers and other people in Swindon have always referred to the company as Garrard's, but what its products were called changed over time, particularly as technology changed. The company made turntables which were later called decks, along with record changers or autochangers, which could also be called record players or, less accurately, a hi-fi.

Garrard's Swindon operation was split into three sites, with the main Newcastle Street factory - where the B&Q/Halfords Fleming Way superstore now stands - housing production lines plus research and development (R&D) facilities. Blunsdon was a press and moulding shop and the Cheney Manor premises - known to Garrard's/Plessey workers as Building 103 - was a factory producing the cheaper range of turntables. This is now owned by Deloro Stellite.

Such was the quality and stability of Garrard's turntables that the Swindon factory devised a novel way of showing off just how reliable they were in extreme situations. Some were fixed to walls and played at right angles to the ground while others were screwed to the ceiling and played records upside down.

For many years the Newcastle Street factory had a shooting range underneath, where workers could go to practise rifle shooting during breaks.

Swindon probably had the highest concentration of owners of quality Garrard's units of anywhere in the world as many workers were able to build their own machines - mostly legitimately. The company had a policy of stripping down and thoroughly testing turntables and record players at regular intervals - and bits from these test units were often salvaged by factory workers, many of whom had the necessary skills to put them back together.

Most Swindon people who didn't work for Garrard's would have found it difficult to afford the top-of-the-range models that the firm was renowned for - and even ingenious thieves were left frustrated in their attempts to own one. The majority of models were destined for export and as most of these were intended for the United States, which has a different electrical system, any stolen in Swindon were likely to be useless in Britain. They simply didn't work - and conversion was so difficult that it was impractical.

Thanks must go to Terry Sullivan of Loricraft Audio (who now own the Garrard name) and Marco van Dijk, who kindly gave us permission to reproduce many of the pictures you can see in this article. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||