|

|||||||||

Lord Joffe Interview

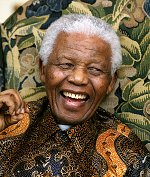

On the day the late, great Nelson Mandela sadly died, here is the interview we conducted with his former lawyer & Swindon resident Lord Joffe in 2008

The Swindon man who fought for Nelson Mandela's freedom

27 June 2008

As Nelson Mandela celebrates a star-studded 90th birthday in Hyde Park tonight, we speak to one man in Swindon who once feared that the South African would die in jail.

Lord Joel Joffe, the human rights lawyer who defended Mandela in the famous Rivonia trial of 1963-4, lives in Liddington, Swindon.

And we caught up with him to hear his inspirational story.

Growing up in South Africa, you obviously witnessed the terrors that were happening there, but what was it that made you dedicate your career to human rights?

In South Africa in those days you grew up in a society where blacks were really seen as servants, and you accepted it as just a part of life. I never thought deeply about it until after I left school, and then just the glaring injustice of what was happening, and the way black people were being treated, drove me to make some sort of contribution. And did you grow up around black servants? Oh yes, we had black servants, I think we had two or three. They weren't badly treated, but they worked hard for us and they certainly weren't treated as equals. So was equality something you had always campaigned for? It was only after I'd qualified as a lawyer. I didn't really campaign, I just defended people who needed defences because of their political beliefs. But it must have been very difficult to speak out, with the apartheid? I wasn't terribly popular with my population. But it wasn't so much speaking out in those days, it was actually defending people who spoke out.

When did you first come in to contact with Nelson Mandela? I first came across him when he was charged with sabotage in 1963. And although I'd met him once before, we were introduced but never even spoke. So I met him really for the first time in the prison interview room in Pretoria. The trial really changed events in South Africa, but it must have been harrowing to stand up against all the corruption of prison staff? I wouldn't say it was a harrowing experience, because it was a great privilege to defend Nelson Mandela and the nine other people who were charged with him. They were all remarkable people, and I suppose I think it's actually easier for a lawyer.

You have certain rights - you can go in to the jails to meet your clients, so you're not really standing on the street corner speaking out. You're just doing your job really.

But how difficult was it to defend him when there were witnesses being threatened by the police?

It was a difficult trial, but a very interesting one. They were accused of sabotage, and what Nelson Mandela and the other accused decided to do was to accept responsibility for anything they had done, so they wouldn't deny their involvement.

What they decided to do was to turn the trial in to a trial of the government. So where they were being charged personally, much of the purpose of the defence was to put the government on trial in the court of world opinion.

So actually this was really the main objective of the accused. They would accept responsibility for anything they had done, and if the court decided to sentence them to death, that would be so. They would not go back on anything they had said.

They would never plead for mercy. They wanted their conduct in the trial to be an inspiration to their followers, and in addition to influence world opinion. And I think that's what they and we achieved.

And do you think democratic countries helped enough? Actually as the campaign carried on, there really was significant help internationally. The UK in particular, because the anti-apartheid movement was very strong in this country. There were boycotts organised against South Africa, and in the end the Americans joined too, and most of the Western European countries. Some communist countries even joined - Russia mainly.

Eventually the pressure from outside was a significant factor in the transfer of power to the African National Congress.

Did you have any contact with Mr Mandela while he was in prison?

Everyone in the world wants to see Nelson Mandela, so I didn't spend long periods with him. But I was in South Africa a month ago, at the end of May, and I visited him at home. I probably spent 45 minutes with him.

How did it feel to go back and see him there? He's a very wonderful man, and he's got great warmth and charisma. So it was again a great privilege to see him. And of course he's very much changed now. At the trial he was a big burly man, and now he's frail, but when he stands up to talk it's all the old flair and strength.

Was your move to England in 1965 a result of the trial? Well actually it was a result of the political situation in South Africa, and we had decided before the trial to emigrate to Australia. After the trial I was not very popular with the South African government, and I'd handled a number of other political trials as well. So they took away my passport, and eventually after the trial they let me leave on what is called an Exit Permit - where they let you go out of the country, on the condition that you never return.

And then the Australians, who had previously been so keen for us to go there, decided that they didn't want me in Australia because they had a whites-only government in those days and they worked quite closely with the South African government, which also thought it was only for the white people.

So when the Australians wouldn't let us in to Australia, we ended up here. I guess I was considered an undesirable immigrant.

And what got you involved with Hambro Life in Swindon?

Before Hambro Life there was another company which was started by somebody I was in university with - Sir Mark Weinberg as he is now - and Mark had just started an insurance company called Abbey Life. It was a tiny company, and he asked me to join him.

When I was here I was still trying to get in to Australia, but the government were reviewing the situation, and I went to see Mark, not with any intention to get a job, and it looked like he was going to be expanding rapidly, so he offered me a job.

I then phoned my wife Vanetta, who was in South Africa still with our two babies, and she said she was so fed up living back at home with her parents and the children, that I should take the job. So I took the job and they came over here to join me.

And you were still so involved with human rights, with your time as Chair of Oxfam. Did this help keep a link with South Africa? I've got a charitable trust so I support Excellent Development and I support a number of agencies. I'm still a trustee of the Legal Assistance Trust of South Africa, which is to support human rights in South Africa.

I suppose I'm getting old now, but I'm still obviously very interested in human rights.

Were you also involved in supporting local causes?

When I first came over I worked with the Swindon Voluntary Services Council, and I was amazed at the amount of voluntary organisations in Swindon. And you've still got your charitable trust? Yes, I've still got the trust, and of course I've spent three years in the Lords, where I've spent a lot of time working on euthanasia. That's obviously another controversial issue. Well one does what one believes is right, and I see it as a matter of human rights as well that people should be able to make decisions on how to end their lives, just as they make decisions during their lives. And was there any particular experience that made you want to back that cause?

No, it's quite odd actually because many people ask me that. When I came to this country and read some literature about what was then called the Voluntary Euthanasia Society, and it seemed to make sense to me. I took out life membership when I was about 35.

I did nothing but get their bulletins and felt guilty that their postage costs would be more than what I'd paid to join! But then they decided it would be a good idea to get a Bill introduced in to Parliament, and they went through their records and they found my name, and they approached me and asked if I'd introduce the Bill in to Parliament.

And that, as I say, used up about three years of my life. And it certainly got the item on to the agenda there.

You've been busy with your books as well – and you only published Mandela vs. The State last year.

Yes, but it was actually written when I came here to this country in 1965 and while I was waiting trying to get a job, I had a lot of time on my hands, so I decided to write the book – essentially because I thought that Mandela and the other accused would die in jail and it was important that their courage and integrity should be remembered, and as it happened they didn't need me to write about it!

[The book includes a foreword written by Nelson Mandela in which he describes Joel Joffe as 'having the most extra-ordinary vantage point on the Rivonia Trial... based on an intimate and deep grasp of what happened in court.... and is a remarkable piece of contemporary historical writing'.]

And today the biggest human rights issue is with Mugabe – what are your thoughts?

It's appalling actually. And it's good to see at last the rest of the world is coming round to recognise just how appalling it is, and how evil the system is.

I mean, Zimbabwe is far worse than South Africa ever was.

He's a monster, and actually I think he should be charged with genocide. But of course you can't charge him in Zimbabwe, you've got to get him out of there.

Yesterday was the first time Mandela spoke out about Mugabe. Why do you think he kept his silence for so long? When Mandela retired from politics, he made it clear that he would not make statements about the rest of the world. That was the job of the South African government of which he was not a part, and he didn't want to do anything to undermine his successor, Mbeki.

So he deliberately held back, and would never criticise Mbeki because he felt that would undermine him. For example, in Aids he found a way of expressing his views on what needed to be done, without undermining Mbeki - who had this mad idea that Aids was not an illness, and more to do with malnutrition.

And likewise with Mugabe and developing South Africa, Mandela never though it was right for him, as someone who was not a politician, to be making statements criticising what was happening.

But clearly the pressure over here has been such, and the evil and injustice of what is happening in Zimbabwe led him to very briefly say what he thought.

It was a criticism of the leadership in Zimbabwe, and it was very important because he has a lot of influence with the other African leaders.

The Ghana Broadcasting Corporation suggested that Mandela may have been persuaded to speak out by the British government - would you agree? I think he would have wanted to be saying something and was holding himself back. When he saw things weren't quite as terrible as they were in Zimbabwe with the selection and all the violence that had happened, he spoke while he was over here.

I don't think this government would've persuaded him. Nelson Mandela doesn't take instructions from anybody. With the situation in Zimbabwe, do you think people look to Mandela and his fellow accused for inspiration? Yes, I think they are really models for all civilised people. You've dedicated your life to human rights - do you feel you've really made a difference? I think one tends to make a small difference. Actually I dedicated a fair amount of it to earning a living with Hambro over here. Although I was pretty good at it, it was still only a job for me, which turned out to be one which made a lot of money! So I was able to set up the charitable trust.

I don't think I should get much credit for my human rights work in the sense that there are so many people out in the field actually really suffering and really losing their lives, lying in jail and being tortured – those are the real heroes.

But they rely on people like you to get their message across. You can do useful things I think, but I just don't want to paint a picture of myself as a suffering hero. I've got to ask about your Desert Island Disc – how did that come about? The BBC wrote to me but I told them at first that it wouldn't be particularly interesting, but in the end I did it and it was rather an interesting experience. As it happened, it worked out well. So Mandela's coming up to 90 and there was a time when you thought he would die in jail. It must be amazing to see him here celebrating with thousands of people? He's the world's most famous person. He is just so remarkable, and yes it's a fairytale ending. But it's the fairy who really suffered in order to get the recognition which he deserves.

So it's easy in all the things that go on in the world, to sometimes despair, but you find a large number of really fine, good people.

And that's one of the real privileges of working with someone like Oxfam where you travel around the world and meet the people who are trying to create a better life for their families, and where you get an opportunity to contrast the way we live in this country with the appalling poverty and lack of food, lack of education, and lack of health in so many parts of the world.

Mel Turner-Wright |

|||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||