The Yanks are Coming!...

Memories of the staff from the US Army's 203rd General Hospital reveal life in Swindon in the run-up to D-Day

The site is dedicated to the work of a miltiary unit, called the 203rd General Hospital, which was set up to tend to casualties of the Normandy campaign. Its staff of more than 600 stopped off in Swindon for a month in the run-up to D-Day (June 6, 1944), and their written memories, which were first published in print in the 1990s but are now partly available online, paint a vivid picture, from an American perspective, of life in Britain during the war. And they have the added value of including not just the testimonies of American service men, but also service women, thanks to the nurses who came over with the hospital.

They were by no means the only ‘Yanks’ in Swindon. After the Americans entered the war in December 1941, a steady trickle of GIs began to arrive in Britain, with the very first in Britain being posted to Chiseldon Camp.

Thousands of others were billeted in and around Swindon, and countless more were transported through the town, which became even more of a hub of the railway network than in peacetime, especially in the lead-up to D-Day. There was even an American Red Cross club in Cromwell Street, which opened in June 1943, a full year before the invasion began. The 203rd wasn’t even the only American mililtary hospital in the area. The 302nd Station Hospital was established at Lydiard House, to care for casualties from the 101st Airborne Division, which was made famous by the TV series Band of Brothers. There was also the RAF hospital at Burderop (later renamed the Princess Alexandra Hospital), which received American casualties, including the first D-Day wounded, who were transferred there in ambulances after being flown into RAF Lyneham, exactly a week after D-Day.

The 203rd General Hospital was different because, rather than being accommodated within their unit, staff were billeted on apparently unsuspecting local people, in private homes, mostly in Old Town, Swindon. The unit, which was formed even before the Americans officially entered the war, came to Swindon en route to Normandy, and would eventually back up American forces all the way to Paris. Although they only stayed in Swindon for a month, they made a big impact on the local population – and vice versa, as the testimonies reveal.

Old Town home-from-home

The homeowners who took them in – generally people with spare rooms – had no choice as they were ordered by the authorities under wartime regulations, and in some cases appear to have been given very little advance warning of the Americans' arrival.

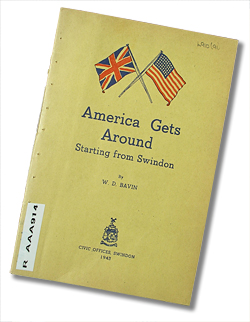

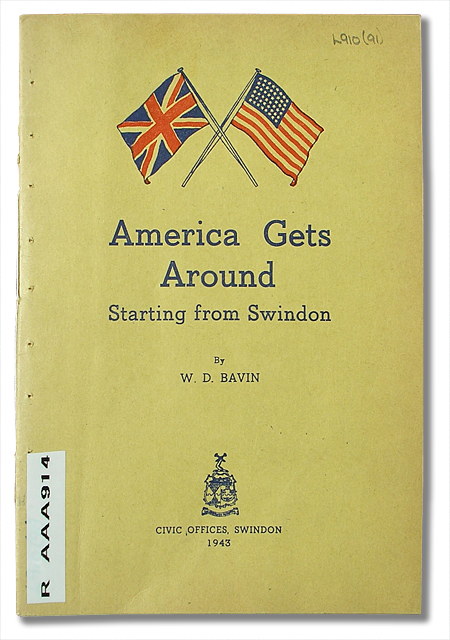

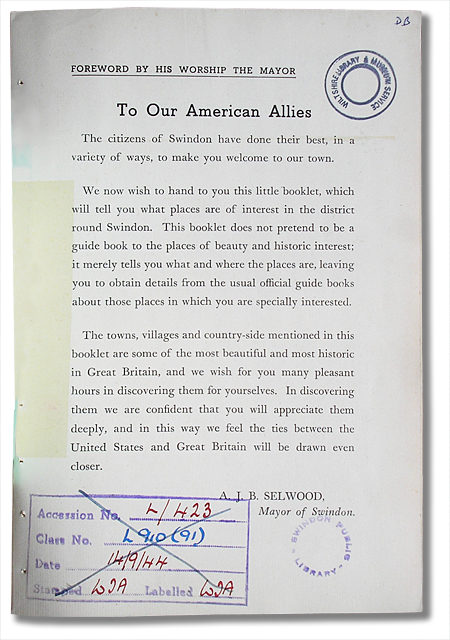

Their guests were aware of this sensitive situation, but if they felt awkward at first, many developed excellent relationships with their hosts, who were mostly more than happy to help their allies, once they got over the initial shock. Ironically, if spare rooms were available, it was often because its usual occupant had himself (or even herself) been called up for military service. Swindon Council had already paved the way for an influx of American visitors with a booklet, published in 1943 and called America Gets Around: Starting From Swindon, which was intended as a guide to the area, which servicemen could utilise during their spare time, and they were encouraged to explore beyond Swindon. The staff of the 203rd General Hospital duly arrived in Swindon by train on February 17, 1944, four months before D-Day, having moved on from a temporary camp at Petworth in Sussex.

While personnel were dispersed to their billets, an administrative headquarters was set up at 25 High Street (which no longer exists). But the Bradford Hall in Devizes Road – then a dance hall and destined to become Swindon Arts Centre in 1956 – became the staff’s main focus, particularly as three tents were erected as a temporary mess, on land behind the hall. The unit stayed in Swindon for exactly a month, continuing their training, exploring the local area and striking up good relationships with Swindon folk. For most it was their first taste of British life, and the added experience of actually living with local families clearly produced memories they would never forget. Various veterans of the hospital contributed to a collection called An Anthology of Memoirs of Service with the 203rd General Hospital, WWII, produced by the US Medical Research Center, and several recall memories of Swindon. One thing they all remembered was the combination of one of the coldest spells in living memory in Swindon, and a lack of fuel caused by coal rationing. And this unlucky situation was made all the more shocking because the Americans apparently expected homes to be centrally heated, many expressing incredulity at families' reliance on ‘open hearths’ (which wouldn’t be uncommon in Britain until the Seventies).

Elinor Bird, a nurse, recalled: We would sit beside the fireplace at night, reading and listening to the radio. After the news and Big Ben had tolled 10pm, we would go to bed. And I was always welcome to bring in my friends. She loved to play cards and would play for money and she always won! Our baths were limited, as was the hot water, so I would use the water from the hotwater bottle to wash in the morning. They were afraid to use much water as they feared they might need it for fires set by bombs. Another nurse, Harriett Lecours, wrote three letters home to her parents during her stay: 26 February, 1944 A change of scenery. We have moved and are now billeted in English homes in ones, twos and threes. My friend, Esther Meng, and I live in this little room on the third story in a rather nice home. No heat, of course. Although they gave us this little electric heater, but I can still see my breath in the room. They asked us down to sit by their fireplace, which I did this afternoon. Considering they have no choice in the matter of taking us Americans into their homes (a spare room made them eligible for American intruders), we think this family has been very hospitable. There is an elderly mother, two grown sons and a housekeeper who comes in daily. The mess hall is about six blocks away - in tents. We get our food in a building and carry it outside and into a tent which has one gas stove for heat. Then we have this hall that is sort of a Headquarters - called Bradford Hall. When we go there, we all compete for a place next to the stove. My friend Tilly Ryan says she has ‘chili blains’ all the time. It is so very cold! 27 February, 1944 We are now quite comfortable sitting with our ‘family’ in the afternoon or evening by the fire - the one warm place in the house. In exchange for their hospitality and tea, we give them our rations of cookies (biscuits to them) and matches, candy or anything else we think they'd like, and soap. It is rationed for them. 9 March, 1944 Would look as if spring might find England after all since it is a lovely day outside, although quite cold. As usual, I'm hugging the fireplace in the drawing room. The cat is asleep in one chair by the window in the sun and Mrs Masters is in another chair, soaking up this precious bit of sunshine. I'm eating a lemon with salt on it. A large supply came in for the civilian population and I had once mentioned I liked to eat them with salt. So nothing would do but for me to have one. Also at mess this morning we had fresh eggs and fresh oranges. Our first since leaving the ship. We certainly have to toe the ‘GI line’. Sometimes it is as if we never do anything right. Either our hair is too long, the skirt too short, our coat not buttoned properly, always something. Our Chief Nurse enforces all the regulations and we mostly comply… but grudgingly. At night, we usually listen to Lord Haw Haw (this was a man named Joyce) on the ‘wireless’. He comes on from somewhere in Germany. He talks about "the vulgar Yankees" and "the American Army of Occupation in England" and "the Jews of Wall Street." He says the US is just playing Great Britain along for its own benefit. Now - a few items you might send me, and please wrap them in some paper sacks if you can: about six or eight clothes pins, some rubber bands, some Dorothy Gray pancake makeup, and some toothbrush fillers. I can use the sacks for shopping. They have none here, of course. And I forgot to tell you that I bought a bicycle. It is wonderful to have one, and I can ride it to the mess hall. Martha Belew and I went to tea out in the country the other day. A nice lady asked us to come to her house. It was a thatched cottage and she said it was 300 years old. No central heating, of course. We wore warm clothing.

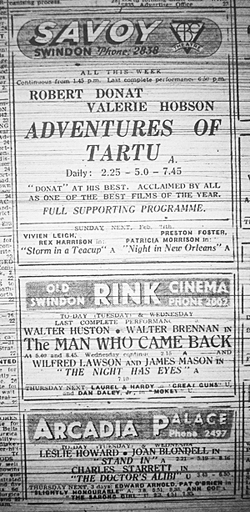

Another (unknown) author gives more insight into life in Swindon during this time, and how it differed from what the Americans were used to: In addition to an American Red Cross Club, it also had British and Canadian Clubs. Some movie houses were found in the center part of town. Whereas the American terminology for orchestras appearing in person is ‘swing session’, the British versions of them were designated ‘concerts’. So, at first, GIs did not go to these so-called concerts until they became aware of what they really were. These concerts were always held on Sunday afternoons and always played to packed houses. There was not a GI who had not, at one time or another, had English ‘fish and chips’, if he had been to the U1C taverns that closed nightly around 10.30pm. And thereafter until midnight, long queues were seen forming outside of ‘chips’ shops. This was a welcome diversion from the usual GI bill of fare. During its stay here, the unit was billeted with private families (officers as well). The unit arrived in Swindon in the late afternoon and it was some hours later before sufficient billets could be obtained as sleeping quarters. The English bobbies were very co-operative in this respect in obtaining necessary quarters for our unit. There were very few instances of complaints by homeowners who had to billet military personnel. These complaints were quickly retaliated with warnings by the police. However, many of the men felt self-conscious about intruding in this manner. Billeting in private homes did not necessarily mean cots or beds. It was merely a matter of luck being billeted in a home that had an extra bed. Otherwise, it was a matter of getting used to the floor. Eventually, quite a few friendships between the English and the GIs resulted from this situation. It is generally known that English people love their tea, so many a GI who was billeted with an English family had to get used to the custom of having tea at 7am in the mornings. English homes were heated only by open hearths, so it was impossible to remain in the homes long because of the cold weather, which was still prevalent. Many a GI preferred to spend the evening in the Red Cross Club downtown, or a pub, in preference to the coldness of the homes. Coal was a scarce commodity. Sleeping quarters only were provided in the homes. The mess hall was situated in an area adjoining a former dance hall. The dance hall itself was set aside as a recreation room, which was not much used by the personnel because of the coldness. There was a lot of time spent visiting around town since the hospital was not yet operational. And in the mornings, just before chow time, GIs could be seen coming out of different homes. However, there were many who preferred to remain in bed as there was no means of checking roll.

Arriving two days after the General Hospital staff, a Red Cross detachment also came to Swindon, and reported similar experiences, including a not very auspicious start: The first night in Swindon was a rough one - some of the girls found themselves sleeping in bathrooms, on cots with lumpy straw mattresses and on window seats. What we'll all remember about our stay in Swindon is the bitter cold. Until the day we left Swindon, few of us were ever warm. We all began to take tea every afternoon around three or four o’clock, and we frequented such places as McIlroy’s, The King's Arms, The Goddard Arms, and some of the little teashops nearby. A lot of us learned to have a small drink before lunch, the excuse being that this was the only way we could feel even momentary warmth. We went to innumerable movies, good and bad, because we found that the cinemas were slightly less cold than our billet or out on the street.

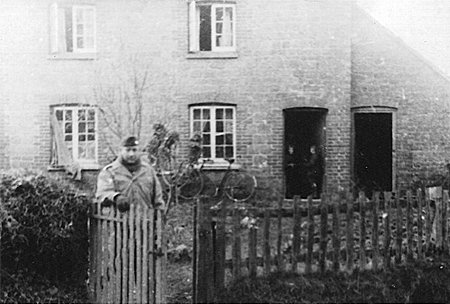

Perhaps the testimony that is most revealing about the impact of the Americans on the population – especially given the apparent short notice afforded their hosts – comes from Dan Leary, who wrote: We are met at the Swindon rail station by a group of British bobbies (cops) and are trucked to scattered sections of the city. Swindon, being a railroad center as well as a producer of manufactured goods, has a wartime population of about 100,000. Many of us are deposited in streets of middle-class workers’ row houses. Officers, including nurses and a few enlisted men, find themselves in more affluent areas. The majority are split up and ushered by the bobbies into civilian homes as the people are quickly read wartime orders covering the quartering of military troops. Some of these people are startled and confused at the prospect of opening their homes to foreign soldiers whom they know nothing about, only what their government has told them over the radio, or information from the newspapers. George Yoder and I are practically shoved inside a row house to face a rather frightened elderly woman who is apparently alone. At first sight of the two of us, she mutters incoherently and bolts from the room and up the stairs, to the safety of her bedroom. We can hear the movement of heavy furniture against the door. We must have appeared as monsters from another world with our great steel pot on our heads, the bulky GI overcoats, the masks, a huge pack on our backs and the always overloaded barracks bag. No wonder the poor soul fled the scene. Bitter cold that seemed to penetrate the bulk of clothing that we wore, plus a pitch blackout in an unfamiliar city left no other alternative but to simply lay down on the floor for what was left of the night. The next day our situation improves when we are re-billeted with an extremely co-operative family who happen to live just around the corner from the unit's temporary HDQ and mess, a one-time public building called Bradford Hall. Dan’s other memories of his stay are in a shorthand form: Hitler's secret weapon, the bloody damp cold that we never get used to... Walking the ancient streets until a tea room or a pub would open… Getting up in the middle of the night when an air raid alert sounded and shuffling down to the nearest public shelter… Most of us didn't want to leave our warm sacks to protect our lives, but we did it to please our hosts… After a couple of these inconveniences, we say "to hell with this" and dig deeper into the old sack… I keep telling 'em up at HDQ that Hitler and me ain't mad at no-one!.. Sharing our precious PX rations with our civilian hosts… The cinemas in Swindon that could have served as refrigerators… Favorite pubs - McIllroy's, The King's Arms, The Goddard Arms and The Red Lion… Wearing GI long johns… Fish and chips served in a used newspaper… “Pub crawling" and the long-lasting friendship with the people with whom we lived… "You bloody Yanks are going to sink our island what with all of the material that is being stocked around our countryside. The only thing holding us up are the barrage balloons." The unit finally moved out to Broadwell Grove, two miles south of Burford, where the purpose-built 834-bed hospital that was under construction began to admit casualties. It continued to receive patients after the D-Day offensive began, but the hospital and its staff were transferred to France at the end of July 1944. Swindon and its attractions were certainly still in their minds after they arrived at Burford, because one testimonial writer hinted that he and his colleagues were already missing the town’s favourite beer, Arkell’s 3Bs.

He noted that many of his colleagues had bought bikes during their stay in Swindon, and that 3Bs was generally understood to stand for "Beer, Bicycles & Blackouts”.

With special thanks to Lois Montbertrand, who created the 203rd General Hospital website (http://hospitals.med-dept.com/203rd.General.Hospital/) in honour of her father, Captain Robert L Shiner, US Army Dental Corps, 1938-1946, and his unit. America Gets Around reproduced courtesy of Swindon Central Library. |

|

||||||||

|

D-DAY |

||||||||

|

RAF Blakehill |

||||||||

|

Alan Fowler |

||||||||

|

Swindon on D-Day |

||||||||

|

Flying Nightingales |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||