Part I - the War at home

Swindon and World War One

They were to be, without question, the worst four years in the town's entire history.

Yet the people cheered when the hooter blew and - something that makes what is already a fascinating story all the more remarkable - they never really stopped cheering, regardless of how horrific the news got. But to understand why Swindon's experience in the war provides such an eye-opener on a unique period in our history, you first need to briefly put the First World War into its proper perspective.

Your country needs you

It isn't generally realised that twice as many British people died during the First World War than in the Second World War - and it's just about impossible to comprehend the suffering of battles such as the Somme, which stand as easily the bloodiest and probably the most futile in Britain's history. It was bad enough at home in a town where wives and children were deprived of husbands and fathers for four years - and sometimes forever - and where conditions eventually became so chronic that rationing was introduced.

They would even come to call it the Great War - not necessarily just because of its extent, but also because to them it was a great crusade a just and glorious war in which God (as he always seems to be whenever any army goes to war) was on their side. We know an enormous amount about what happened in Swindon between 1914 and 1918 because it is recorded in great detail in a fascinating book on the shelves of Swindon Reference Library. Called 'Swindon's War Record', it was prepared for Swindon Town Council by a Mr WD Bavin who started work on it before the war had finished and published his work in 1922. He begins by recalling what happened when the Works hooter signalled the start of the war: 'Within a few minutes, excited crowds were streaming towards the Park in New Town or the Old Town Drill Hall, where the men were promptly reporting themselves.' These were local territorials of the 3rd Wessex Brigade of Royal Field Artillery part-time soldiers, now pressed into full-time defence of the Empire. Next day, a contingent of 80 men assembled at Old Town Station where they were met by the mayor and cheered by a crowd as they caught the train to Portsmouth, eventually bound for India.

Another day later, ten more blasts on the Works hooter called the Swindon Squadron of the Royal Wiltshire Yeomanry a part-time cavalry unit to the station where they 'got away amidst the cheers of a large crowd'. The Yeomen would soon be fighting in France and Belgium.

The majority of local men were railway workers and probably would have avoided active service in the Second World War because their work was seen as vital, but few such 'reserved occupations' were recognised in the First World War. Swindon consequently provided its share of soldiers and even sailors like any other major town. In fact, the military tradition in the county meant that there was already a sizeable part-time force in the area, along with a large number of reservists. These were men who had signed up for the army and, even if they had served their time, were still bound to be called up in times of war. Many local men had just returned from their annual summer camp when war was declared and they were called back into uniform.

There was also a National Reserve and later a Volunteer Training Corps a kind of Home Guard which included men who might be unfit or unable to sign up for active service, perhaps because they were the wrong age. They were involved in the defence of the Home Front against possible invaders and since this included strategic points along the railway like bridges and tunnels, many from the large local population of railwaymen and ex-railwaymen naturally stepped forward. So, in many ways, Swindon men were mobilised instantly and in force, but the authorities wasted no time in instigating recruitment drives for those who weren't already in uniform. 'The schemes at first devised were purely voluntary in character,' recalls our key historian, WD Bavin, 'and compulsory national service was as yet undreamt of.'

By October, 2,634 Swindon men were in these various branches of the forces around 2,000 of them having signed up since the outbreak of war. This was around half of those who would eventually serve, as WD Bavin's history - which names every one - reveals. A total of 5,383 men from Swindon fought in the war - and 920 of them were killed.

The war effort back home

Swindon also played host to thousands of other soldiers as the town received a huge influx of troops from other parts of the country, as soon as war was declared. Many of them were billeted in local homes - up to five or six to a household - and several schools were requisitioned. Sanford Street was converted to a hospital and Clarence Street used as a barracks, while a large camp was established at Chiseldon.

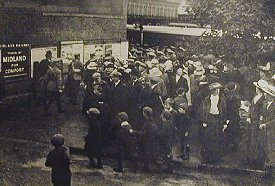

A feature of these very early days of the war were the long columns of troops which could often be seen marching across town, from one station to another. A measure of the scale and swiftness of the mobilisation is that during just three days in August - the first month of the war - 45 trains left Swindon Station, filled with troops. 'It would be difficult to reproduce the gaiety and eager excitement of those days,' says WD Bavin, who also records how many commanders later wrote to Swindon to thank the town for its 'overwhelming hospitality'.

Welcoming refugees

Refugees from Belgium were welcomed just as enthusiastically when they started to arrive in September. Thirty homes were designated 'Belgian homes' for the 350 refugees who came to Swindon. They included 'a little girl of five years of age whose tiny arm bore the cruel gash of a German sabre'.

Swindon's response to the needs of Belgians is only one example of the staggering contribution of the town on the Home Front, which always matched and often exceded the enthusiastic national war effort. The town never lost its ability to call a mass meeting, elect a worthy committee and then go beyond the call of duty in its self-allotted tasks.

Tending for the wounded

The war was less than a week old when a wave of enthusiasm for the activities of the Red Cross swept the town.

The GWR Medical Fund baths in Milton Road were rented so that they could be converted to a hospital that would admit 1070 patients before it was closed in June 1915, and a new hospital opened at Stratton in 1917. Meanwhile, railway workers wasted no time in doing their bit. On August 24 and 26 three weeks into the war 'the first two of a magnificent series of ambulance trains left the Swindon Works'. Folk queued four deep to go into the factory and see them and because nobody ever wasted an opportunity to raise funds for a worthy cause, people were charged 6d (2.5p) for the privilege. The birth of new industries It has to be said, however, that Swindon was doing rather well from the war in its earlier years. In 1915 there was 'plenty of work and none too many hands for it' and new industries were founded which would have an important influence on the development of Swindon - not only after this world war, but also the next. In 1915 the Imperial Tobacco Company opened up a new factory and, although it would be commandered for munitions work in 1916, it would eventually become a major employer as WD & HO Wills. A new factory employing 50 girls also opened up in Newcastle Street, manufacturing rope and sails, while McIlroy's, the now sadly-missed department store in Regent Street, prospered after it received an order for 45,000 beds from the War Office in 1914. A third of the order was to be manufactured in Swindon, creating 250 new jobs in two large workshops. 'This was the beginning of a period of unheard of financial prosperity for boys and girls, a not entirely mixed blessing,' said WD Bavin.

When they did get time, one highlight during the war years was a series of free shows at the Empire Theatre. Organised by a local 'man of the people', Alderman James 'Raggy' Powell, they were laid on for the wives and children of men in the forces, and provided a couple of hours relief away from the worries of the conflict. A feature of these get-togethers was that a photograph was taken of all those who attended, with copies sold to raise funds for the war. Digging for victory When it was noted that the Navy were suffering from a lack of fresh fruit and vegetables, a national appeal was launched for local collections - and Swindon leapt into action, guided by the inevitable committee. In the first month, no less than 80 tons of food was collected, with the most celebrated volunteer being Floss, a collie-dog belonging to a Mr Trineman who wore a collecting box on its back in the Borough Market. The dog was so successful that it was later drafted into Highworth Market to do the same job. Meanwhile, schools organised 'potato days' when pupils each brought in one potato - and soon the General Secretary of the National Vegetable Production Committee was singing the town's praises. 'If the work of our various branches were measured by tonnage,' he proclaimed, 'I think that our Swindon branch would be in top rank.' Servicemen were also made to feel at home at the Town Hall which was converted into a 'soldiers' rest' - mainly for the large numbers of men from local army camps who flooded into the town at weekends. These included 'Bantams' - men who were found to be under the regulation height for the army and, not to be outdone, had formed themselves into a special unit. WD Bavin unkindly noted what a comical sight they made around town, especially when accompanied by their 6-foot-tall sergeant. Sadly, the town's hospitality towards the soldiers came to an abrupt end in November 1915 when Swindon was made out-of-bounds to soldiers because of an outbreak of scarlet fever. Continued fundraising Nothing could dampen the enthusiasm for fundraising, however, and a feature of all the war years were flag days. In the same way that we now celebrate Poppy Day, small flags were made and sold, often in the colours of a particular country who would receive the funds. In 1915, flag days for France, Serbia, Belgium and Russia our allies received an average of £200 each. The good causes eventually varied enormously in 1917 there was a flag day for wounded horses and in 1918 one to provide 'smokes' for servicemen but Swindonians' generosity hardly faltered. This was true despite the decline in the quality of life in the town during the war years. The annual 'trip' week, a traditional holiday for railway workers, was abandoned in 1915, Swindon Town Football Club reverted to amateur status and food rationing finally came into force in 1917. Still money poured in from fundraising. In May 1918, a special Tank Week was set up partly so that Swindon could marvel at the new invention that it was hoped would turn the tide of the war, but also so that townsfolk could be persuaded to part with even more money to finance more tanks.

HM Tank No 113, named 'Julian', was the centre of attention in the Market Square in Old Town and the mayor kicked off the fund with a donation of £50. 'Huge crowds lined the streets to watch Julian's progress to the Town Hall' which included smashing its way through a barrier of sandbags and wire which had been put in its path. Children were allowed to 'peep into the mysterious interior' if they bought a War Savings Certificate. If they weren't raising money, they were collecting eggs, led by Mrs T Arkell who was the president of the local branch of Eggs for the Wounded. The operation was masterminded in Stratton and drew support from Swindon and across the area. The branch would eventually collect 161,651 eggs the eleventh highest number out of 2,000 depots nationally. Celebrating the peace When peace finally came in November 1918, Swindon allowed itself a day of celebration, secure in the knowledge that few towns could have done more to support the country's heroes. WD Bavin noted: 'November 11th will remain one of the greatest days in the annals of civilisation.' 'Probably Swindon never saw a more delighted crowd than that which quickly thronged the streets after the news became known. 'Although the afternoon was dull and marred by drizzling rain, nothing could damp the gaiety of the demonstrators or spectators; nearly all were bedecked with ribbons and miniature flags.' The Mayor of Swindon thought it fit to telegram Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, the supreme commander of the British force to assure him of Swindon's 'most heartfelt and lasting gratitude'. Today, Haig is blamed by many for the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of British soldiers in futile battles, so the fact that the mayor thanked Haig for 'the magnificent services you have rendered to the Empire' - when Haig should have been thanking Swindon - is another powerful insight into the times. The war ended much more slowly than it had begun in Swindon because food supplies were only gradually restored and because the camp at Chiseldon was a demobilisation centre. Even by January 1919, two months after the armistice, there were still 117 Belgians refugees in Swindon, awaiting repatriation, and it wasn't until April 1919 that the last Belgian family returned home - delayed by the almost total devastation of their home town of Ypres.

Returning soldiers The return of soldiers, however, brought new fears. Unemployment was 'a source of a good deal of anxiety' with hundreds out of work, including many ex-soldiers. They needn't have worried. WD Bavin noted that the rope and sail factory in Newcastle Street had been bought, in 1919, 'by Messrs Garrard & Co for the manufacture of small motors and tools'. It brought with it the hope of 500 new jobs. In fact, the Garrard factory, which would one day make a worldwide name for itself in the manufacture of record players, was one of the foundations of Swindon's electronics industry. Although they couldn't have known it at the time, it was a good omen for Swindon's future prosperity. It may have suffered terribly through four bloody years, but at least Swindon would be a town genuinely fit for heroes in the difficult years ahead. |

|

||||||||

|

Swindon and World War One |

||||||||

|

Part II - action |

||||||||

|

Part III - the Works |

||||||||

|

Part IV - Little Known Facts |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||