The History of Old Town

The story of Swindon is really a Tale of Two Towns

Old Swindon on its hill retains much of the character of the little market town it was until comparatively recently.

Swindon's lively history was conditioned by geography and geology. Midway between London and Bristol and also between the south coast and the midlands the town lies in a broad belt of historic trade routes and highways, from the prehistoric Ridgeway and Roman Ermine Street to the Wilts and Berks Canal, G.W.R. and modern M4.

Early Roman Settlement

Swindon Hill, 500 feet above sea level, attracted settlement from earliest times for its strategic position and excellent water supply. It is a great rock of Portland limestone that lies on top of the chalk hills and clay valleys of North Wiltshire. The Romans discovered it, quarried the stone and shipped it down to their settlement below the hill at Durocornovium on the main road between Silchester and Cirencester.

The recent discovery of a complex of sanctuaries and temples at Abbey Meads near Blunsdon indicates both considerable settlement and religious significance (see link below).

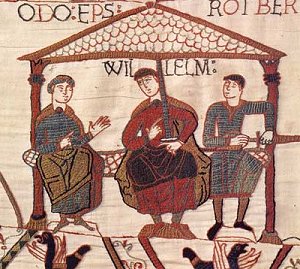

After the Romans left, Saxons lived on the hill, and named it. A chieftain's long house and a cluster of huts once stood where Saxon Court is today, behind Market Square. In 1066 Swindon was sufficiently valuable to be given to the Kings half-brother, Bishop Odo of Bayeux, and a hundred years later the Norman Church of Holy Rood was granted to Southwich Priory.

An historical tour of Swindon should begin at the ruined church, whose chancel and gaunt six-sided pillars remain. Below the high churchyard wall it is easy to see a great depression where once the millpond fed the Domesday mill. Church and Market Square are linked by The Planks with its ancient raised and walled walkway.

The market was established by the Earl of Pembroke, Henry III's half-brother, who inherited the valuable Lordship of "Chipping Swindon" in 1254. With "Right of gallows and assize of bread and ale", the Earl or his Steward dispensed justice as well as regulating trade. Stocks and pillory stood in the square, and a ducking stool at the mill pond, while the gallows loomed grimly on the crest at the top of Kings Hill.

Lord of the Manor

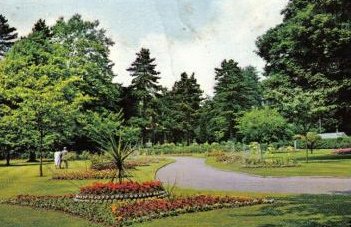

To the north of the old church the remains of an Italian garden and outlines of a great house (note the gazebo nestling in the trees) look out over pleasant parkland and wood and command distant views from the crest of the hill.

The house, "The Lawns" was a fine eighteenth century house built on the site of a Tudor mansion and the home of the Goddard family, Lords of the Manor from 1563 until 1927. The tree-lined drive leads to massive arched gate piers on the High Street facing a range of buildings whose architecture varies from sixteenth to nineteenth centuries. Prosperity really came to Swindon - and the Goddards - with the plague and fire in the 17th Century. Plague closed down Highworth market and brought the trade of North Wiltshire to Swindon market. The rebuilding of London after the great fire led to a new demand for Swindon stone - not, alas, for elegant churches but for paving stone. The streets of London in the 18th Century were paved, not with gold, but with Swindon Stone!

In Victorian times the now disused quarries were landscaped into the attractive Town Gardens. Other fine eighteenth century houses include the red brick Square House, overlooking the market place and 42 Cricklade Street, "the finest house in Swindon" according to John Betjeman, once a home of the Villet family, patrons of the Church and owners of the Eastcott Estate, south of the hill, on which the New Town would be built.

Centre for trade

Swindon's wealth came from the quarry, the market and the agricultural trades - corn merchants, leatherworkers, millers and brewers as well as the widespread but less legitimate trading of smuggling.

Swindon was also a distribution centre for the brandies, tobacco and lace run ashore in the secret coves of the south coast, but destined for the midland counties. A honeycomb of tunnels and cellars lay beneath the elegant houses, humble cottages and busy coaching inns of the eighteenth century Swindon.

Agricultural depression in the 1830s, however, led to outbreaks of violence and rick-burning across the southern counties. Night after night the Swindon Troop of Yeoman Cavalry was called out to disperse crowds and make arrests in the outlying villages. New government-sponsored drainage schemes and modern ideas on fertilisers and estate management developed at the new Cirencester Agricultural College, however, ushered in a period of unexampled prosperity.

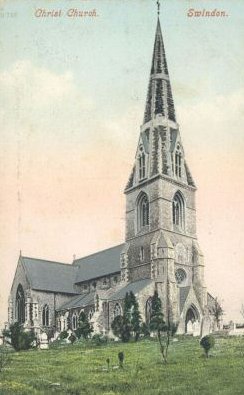

Swindon market was chosen as one of the key indicators of grain prices, and the boom time was evidenced by an elegant new Market Hall on the south side of the Square in 1853, joined ten years later by the spacious Corn Exchange whose campanile still enhances the skyline of Old Town. Its companion on the northern crest of the hill is the graceful spire of Christ Church, built for the growing population by Sir George Gilbert Scott in 1851. In 1864 the age-old rule of Squire and Parson passed to an elected Health Board, which became an Urban District Council in 1894.

Amalgamating with New Town

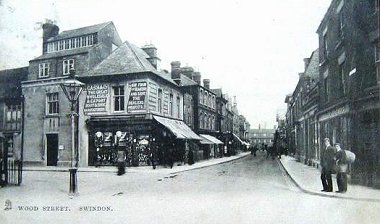

The demand for stone continued with the development of the canal system. Swindon became the junction of the Wiltshire and Berkshire Canal joining Bath and Oxford and the North Wiltshire from Gloucester and Cirencester. With the arrival of the Great Western Railway in 1840 a whole new town was created between the new works and Swindon Hill, entirely dependent at first on the market, shops and services of the Old Town. Mellow Swindon stone was used to build the Railway Village: neat cottages, spaciously set out like a Roman town and still attractive and comfortable today. The ornate 1870s frontage of the Kings in Wood Street, like Pineapple House in Drove Road, demonstrates the decorative skills of Swindon stonemasons. By 1900 New Town was growing faster than Old, and the two came together to form the Borough of Swindon.

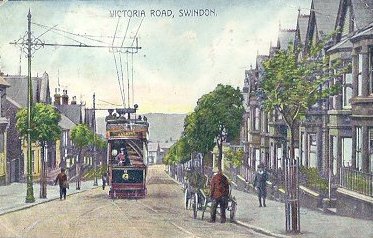

Linking Old and New: the trams on Victoria Hill circa. 1910 But the Tale of Two Towns is not ended, for the New Town and West Swindon show the thrust and style of the new millennium, Old Town, with its rich and varied architecture, quiet courtyards and alleyways, specialist shops and crafts, spacious Lawn Woods and picturesque Town Gardens provides a constant reminder of what William Morris in 1885 called "Ye Old Wiltshire Towne". Photographs ŠThe Swindon Society and used with their kind permission. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Swindon History - Groundwell Ridge Roman settlement | ||||||||

| Swindon History - full list of articles | ||||||||