Brunel and Swindon

Our take on the great man's influence

It's easy to get carried away with Isambard Kingdom Brunel myths in Swindon.

And now that we've celebrated the 200th anniversary of his birth, it's even easier. But if we are trying to find the real Brunel and see how 'the little giant' influenced the town, we may have to be prepared to be disappointed, depending on our expectations. Although Swindon does bear the mark of this great man, it would be wrong to give him the largest slice of credit for turning the town into the beating heart of the Great Western Railway. The Swindon connection is not as strong as some would have us think because only in one respect could the town be said to be in any way a monument to his greatness. Yet, in other ways, his influence on the Swindon story - and vice versa - is greater than imagined.

Out of character

One of the most celebrated books on Brunel - John Pudney's Brunel and His World - bearly mentions the town that would become the hub of the GWR. But there is something important about Swindon in the Brunel story as it indirectly provides us with a rare view of him apparently acting out of character when he deals with the Swindon railway operation. And, though he visited the town on only a relatively few occasions, it still featured in the last letter he ever wrote. Before looking at Brunel's influence in the creation and development of New Swindon, you first have to understand something about the man's character - and his weaknesses. Because even great men like Brunel have weaknesses. For example, if there was an association for people who believed that if you wanted a job doing well you had to do it yourself, then Brunel would have been made its president. It wasn't just that he had faith in his own abilities as an engineer. He also instinctively lacked faith in others - and it wasn't just fools that he didn't suffer gladly. Even the age's greatest engineers were snubbed. He nearly always chose to saddle himself with the burden of even his most ambitious projects rather than charge it to others, simply because he doubted anybody else's ability to meet his own high standards. Add to this a lifelong desire to win fame and immortality and we begin to see a picture of a man who knew he was good and wanted everybody to know it too. Even at times in his life when he experienced self doubt - and there were some - Brunel always eventually came back to a belief that his skill would triumph in the end, and he neither could nor would delegate.

In just a few telling entries and comments, Gooch probably gives us the clearest picture of the great man and certainly breaks through the hype and the image that has grown up around him over the last 200 years. He gets to the core of what Brunel was about - and comes up with a surprising, even touching, footnote about the man. Incredibly, Gooch was only 21 years old when he applied to be in charge of the GWR's engines. Brunel may even have already made his mind up to give him the job before he was offered it during their first meeting in August 1837. He may already have recognised greatness in Gooch, who would become the best locomotive engineer of his generation - and a much better one, for sure, than Brunel himself. It was Gooch, not Brunel, who would eventually rise to become not only the chairman of the GWR and its champion, but also its saviour. One of Gooch's earliest recollections of working with Brunel on the as yet unfinished GWR line (or 'road') reveals how even the hard-working Gooch was struggling to keep pace with his boss. Gooch recalled: 'A person of the name of Murphey had prophesised that one particular night would be the coldest night for many years. As luck, for him, would have it, it came true... but it was anything but good luck for us, as Mr Brunel kept us out all night and it certainly was awfully cold. We suffered dreadfully, but nothing seemed to check the zeal of Mr Brunel in carrying on his experiments to perfect his road.' But their relationship was heading for a watershed - which would provide the exception to the rule about Brunel's approach to his subordinates.

The turning point

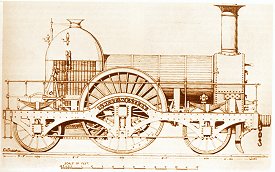

The date was November 25, 1837 and at West Drayton, west of London, the GWR was receiving its first delivery of locomotives from contractors. Gooch's recollection of the day in his memoirs begins with a telling observation on Brunel's personality. 'One feature of Mr Brunel's character,' he wrote, '(and it was one that gave him a great deal of extra and unnecessary work) was, he fancied no one could do anything but himself.' Already worried that the new engines were of poor quality, but nervous of contradicting his boss who had ordered them, Gooch now found himself supervising the unloading of the engines in Brunel's absence. He continues: 'I remember his giving me a scolding for unloading these engines and getting them onto the line without consulting him as to the mode of doing it. I certainly felt no difficulty in the task. There was a carriage sent by road from London which had to be got down the side of the cutting from the bridge, and he sent elaborate sketches and instructions how this was to be done. These took up a great deal of his time and of course were of no use in reality, as there was no difficulty in the work, and circumstances were sure to alter his mode of doing it; but this was no doubt his mistake through life. As a rule he did not get experienced and qualified people about him, and with them it was perhaps necessary, but the work was in consequence often badly done and always expensively.' Brunel's incurable hands-on approach meant that he also lived dangerously - and quite literally. His career was marked by a series of accidents in which he was lucky, on more than one occasion, to escape with his life. One in particular, though, seems to have made him think again about delegating to Gooch - and led him to do something otherwise out of character.

But disaster struck. A rope snapped on the lifting tackle and the shear legs toppled over, killing one man and narrowly missing Brunel himself. 'But for the loss of one man's life,' wrote Gooch, 'I rather rejoiced, after the scolding I had had for doing the work at Drayton without him, that this accident should happen under his supervision, but of course said nothing.' The incident must have set Brunel thinking, while Gooch, for his part, must have known that the time when he would be forced to say something was fast approaching. The engines supplied by contractors, to Brunel's specifications, proved hopelessly inadequate and sometimes downright dangerous.

'When I look back upon that time it is a marvel to me we escaped serious accidents,' Gooch later wrote. The situation came to a head when the directors of the GWR called for a report into the state of the rolling stock, putting Gooch in an awkward position. 'I, however, had no choice,' he remembered, 'and had to make this report in which I condemned the construction of the engines. This alarmed the directors and obtained for me a rather angry letter from Mr Brunel.' But it also revealed a turning point in Gooch's - and ultimately Swindon's - life. Brunel was clearly coming to a conclusion, if he hadn't already reached it, and Gooch's next comment about Brunel's anger at his report is revealing. 'I will, however, do him the justice to say that he only showed it in his letter, and was personally most kind and considerate to me, leaving me to deal with the stock as I thought best. His good sense told him what I said was correct and his kind heart did me justice.' In other words, Brunel had recognised that when it came to locomotives, Gooch knew best. It was one of the very few times in his entire life that he would admit equality with a fellow engineer, let alone bow to somebody else's superior knowledge.

Relinguishing control

Brunel's autocratic attitude to the running of the GWR, and therefore in Swindon, is confined to early exchanges in his relationship with Gooch, but later it seems he was happy to hand over the reins. This goes a long way to explaining why Brunel's subsequent involvement with the mechanical engineering operation at Swindon was so small. For once he trusted somebody - and that man was Daniel Gooch.

And as a consequence, Brunel hardly visited Swindon, but instead left Gooch in complete control. It has been suggested that this situation was virtually forced on Brunel by the GWR board, but the affection that emerges from the two's later relationship seems to be evidence of a mutual respect between the two. When Gooch wrote to Brunel on September 13, 1840, to suggest Swindon as the best site for the GWR's new repair and maintenance depot (see link below), he agreed. When Gooch started to specify his own designs for locomotives to replace Brunel's shoddy ones, he agreed.

From then on, Brunel makes only very infrequent appearances in Gooch's memoirs and diaries, further underlining how he must have been happy to hand over control. Brunel would surely even have agreed with Gooch when he spoke of his own engine designs with the conclusion: 'I may with confidence... say that no better engines for their weight have since been constructed, either by myself or others.' Put simply, it was Gooch, not Brunel, who set the standards and planted the seeds for a reputation for engineering excellence that Swindon and the GWR would enjoy for generations to come - and it has to be said that Brunel was not a great mechanical engineer. Nor a great businessman. And an episode from 1844 would seem to prove both points. Brunel and Gooch travelled together to Ireland to see a novel railway invention in action. It used atmospheric pressure rather than steam as a means of propulsion. Gooch immediately saw the engineering drawbacks but also noted economic problems in what he saw. But both these crucial points somehow eluded Brunel and, worse still, he remained absolutely unshakable in his belief that he was on to something, and insisted on applying the idea of an atmospheric railway to the South Devon Railway. Gooch wrote: 'I could not then understand how Mr Brunel could be so misled as he was, and believe while he saw all the difficulties and expense of it, he had so much faith in his being able to improve it that he shut his eyes to the consequences of failure, and there is no doubt the result of its trials on the South Devon between Exeter and Newton cost the company more money than would have well stocked their whole line with locomotives and worked them also.' It was therefore left to Gooch to bail Brunel out. 'It failed miserably,' he wrote, 'and I was very soon called upon to provide locomotive engines to work the line.' It was perhaps the final indication to Brunel of Gooch's superior abilities - and perhaps even the ultimate lesson to him that his railway engineering skills were lacking, especially when compared with Gooch. But Gooch reveals a growing affection for Brunel as he sums up the project's failure. 'I felt very sorry for Mr Brunel in this matter as it did him some harm, and figures showed it never had a chance to compete with the locomotive in cost and handyness. This is certainly the greatest blunder that has been made in railways.' When, the following year, Brunel was presented with an expensive 'splendid service of plate' at a large dinner organised by his friends, Gooch wrote, privately, that he 'thoroughly deserved it'. But the most poignant entry - and perhaps the most surprising - in Gooch's memoirs and diaries was on September 15, 1859 - the day of Brunel's death. He simply wrote: 'I lost my oldest and best friend in the death of Mr Brunel.'

Lasting legacies

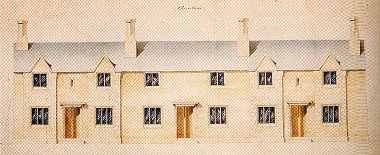

Brunel's legacy to Swindon may not have been his mechanical engineering, but there is one field where he is not merely one of the greatest, but surely the greatest of all - civil engineering. And in this field he certainly made an indelible mark on Swindon. The GWR line from London to Bristol was a masterpiece in surveying and, also thanks to Brunel, was a triumph in track-laying. His route had to overcome prejudice from shortsighted landowners who refused him permission to build it his railway on their estates, but despite the obstacles put in his path, it has gone down in history as 'Brunel's billiard table' because of its flatness. The section from Paddington to Swindon rises at an average of just one in 1,320. This aspect of the line may even be a greater achievement than the iconic engineering structures along the way, such as the arrow-straight Box Tunnel and even the majestic Maidenhead bridge over the Thames. Returning again to Gooch's memoirs, we find the story of the long, low arches of Maidenhead that were said by 'experts' of the day to be unsafe. Today they still survive as a monument to Brunel's skill as a civil engineer but also to elegance in design, and Gooch could not contain his delight when Brunel proved the doubters wrong. Swindon's monument to him is just as pleasing on the eye, if structurally less exciting (and no, we're not talking about the Brunel tower or the shopping centre). Although there is conjecture over who produced the final designs for the revolutionary idea that became the Railway Village, there is no doubt that it bears some of the imprint of Brunel's own hand.

Although he collaborated with architect Matthew Digby Wyatt - who later also assisted with the design of Paddington Station - Brunel conceived the general layout, and many of the original sketches were his own.

He is also known to have taken a strong hand in the design of the buildings of the original works and Swindon station. He maybe famously remembered as criticising the standard of the coffee at the station, but must have taken pride in the development of the works under Gooch, as well as in the rows of workers' cottages whose construction he oversaw.

Swindon Station (as portrayed in the painting 'The buffet, Swindon Station' by George Elgar Hicks: also designed by Brunel - although he often complained about the coffee there!

Sadly, they proved inadequate in the early years because the village was unable to accommodate the mushrooming workforce in Swindon. Even Brunel hadn't foreseen the extent of the role that the town was going to play in the GWR's story, and the town became something of a victim of its own success. Now a century and a half old and beautifully restored, however, the little cottages are a great testimony to his idea. It should certainly not be forgotten that to build a 'model' village such as this, at that time, was a radical move.

It's fitting, then, that the great man's thoughts should have with Swindon, even on his sick-bed, shortly before his death. In what would be the last document written by a lifelong habitual letter writer, Brunel wrote to the GWR directors, urging them to give Swindon's railway workers a day off and free passes for special trains to Weymouth so they could see his ship, the Great Eastern. A man who always intended that his name would be remembered forever, would be particularly pleased to find that the Railway Village is one of the most enduring aspects of the Swindon story whenever we look back on its glorious industrial heritage. And it undoubtedly shows Brunel at his practical best. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Swindon History - full contents | ||||||||