|

|||||||||||

Life in a Railway Village

We explore what life is like living in the Swindon Railway Village 160 years after it was first built by the GWR

Stood in Emlyn Square enjoying the fabulous Brunel 200 celebrations I overheard a young girl who cannot have been more than four years old turn to her mother and ask: "Mummy, did they build all this just for the festival?" She was, I can only presume, referring to the model railway village itself; its remarkably symmetrical parallel grids of distinctive Victorian terraces that disappear into the distance, shielding any traces of modernity from those within.

It was a touching enquiry from the perspective of the youngest generation, which encapsulates the mystique of the model railway village.

In a brave new Swindon, bent on modernisation, the village is something of an anachronism. As buildings are bulldozed and plans to renovate the entire Town Centre progress, it remains frozen in time, a quaint reminder of life in the Nineteenth Century, Swindon's golden age of advancement.

"You do really feel like you're in a time warp," says Julian, who works in IT and has lived on Oxford Street for two and a half years. "It's good that they maintain the old appearance from the outside - they are all listed building - and it is nice to feel like part of Swindon's history."

But Julian, like many others we speak to, points to the convenience of the location - to the town centre, the railway, and his workplace - as the factor that attracted him in the first place.

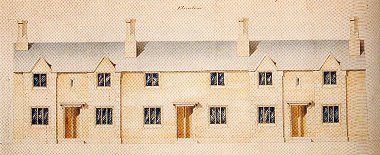

And while it wasn't exactly built with IT programmers in mind, that was the express purpose of the village's creation in the 1840s. The Railway Village was planned when the Great Western Railway Company's 7ft-wide, broad gauge line reached Swindon in 1840. From the outset there was considerable difficulty in providing accommodation for the employees at the Swindon railway works and the solution was to build a model village, using Bath stone (most probably from the cutting out of Box tunnel) and stone from the Swindon quarries.

Driven by commercial considerations (the GWR was not a philanthropic organisation!), builders Rigby's constructed the housing to a standard which they considered would warrant the rent which skilled engineering workers could be expected to pay.

Each road was named after the destinations of trains that passed nearby - Bristol, Bath, Taunton, London, Oxford and Reading among them - and was built in two blocks of four parallel streets, not dissimilar in appearance to passing trains. The Mechanics' Institution and Medical Fund Hospital were built in the nearby open area - named Emlyn Square after Viscount Emlyn, a GWR worker - and all that was left was to house the railway workers in the often overcrowded two storey cottages.

Over a hundred and fifty years on, it is not quite so easy to find railway workers populating the houses, less so any with familiar connections to the original residents.

But we didn't have to look much further than the Glue Pot - a local pub by the truest definition built in 1950 - to find a railway worker refuelling at the end of a hard day's graft.

"I've worked on the railway for fifteen years and it's just fantastic," says James, 40. "I'm actually based up north but we come to these pubs to socialise. It's a good atmosphere and a lot of the workers seem to come here."

Indeed, the three 3-storey pubs - the Glue Pot, the Bakers Arms and the Cricketers - which stand in extremely close proximity on adjacent corners, are further bold symbols of the community spirit of the worker that has lived on. Much like the houses themselves, the pubs are internally identical, each built in close succession as three-storey commercial buildings. Just around the corner is The Bakers Arms, built in late 1840s. Catherine Gould, landlady, took the Arkell's pub over from scratch eleven years ago, but has great respect for its historical value. While not quite like stepping back in time, there is a real feeling of attachment to Brunel's model village in the Baker's Arms, from the interior design to the Great Western Railway notice on the wall reminding patrons of an 8 shilling fine for not fastening the gate.

"We're still very much an old fashioned pub in keeping with the old days," says Catherine.

"Not only does the entertainment very much belong to the old school, from the music to the pub games, but there's a real sense of community and people know this is a pub where you can get anything from stamps to tablets!" "These corner houses were used for foremen and apprentices back in the day and it's fascinating to know this played such a large part in Swindon's origins."

Yet while many do their best to maintain a sense of community and reverence for their forefathers, it is difficult to ignore certain undesirable elements.

"It might look peaceful now but as soon as the sun goes down there are all sorts of problems round here," says one resident. "The noise at night is unbearable and I for one would not dare walk the streets on my own after 10pm. There's a real lack of respect from some people." It is an unpleasant factor but one that most we speak to choose to mention. Yet while such reports would seem to compromise the idyllic historical façade of the 'model' village, it would appear that this has been an unfortunate characteristic from the very beginning. In 1859 Daniel Gooch issued a warning notice about the 'boys of the railway village'. It read:

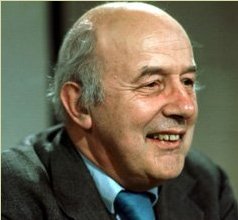

Little, it seems, has changed (although we are not aware of any recent reports of cannons being fired…!). And such complaints aside, we should remain unduly grateful for the railway village, a humble expression of Swindon's illustrious past. One figure who deserves equal mention to Brunel, Gooch or Joseph and Charles Rigby, is a certain Sir John Betjeman.

Were it not for a vociferous crusade by the poet to save the village in the 1960s it would have been duly demolished by Swindon Borough Council, who had applied to demolish it and rebuild. Instead the village was given a statutorily listing as being of special architectural or historical interest. A six year restoration project then bringing Taunton street et all back to their former glory. So while we celebrate Brunel's 200th Birthday let us also raise a glass to Sir John Betjeman, on this, the one hundredth anniversary of his birth. |

|||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||