Lydiard House and Park

Swindon's stately home

Local folk could have been excused for thinking that members of Swindon Corporation were making a huge mistake in 1943 when they bought Lydiard House.

Britain was at war and yet the council was buying a run-down stately home with a chequered history that - even if it could somehow be restored to its former glory - would only ever be in the third division of England's great houses.

Lydiard is certainly no Blenheim, Longleat or even Bowood, but, half a century later, it is clear that the council got themselves a little gem. Put the house in the context of its 244 acres of parkland and the special little church that stands in its shadow and you have something that is often underrated by the majority of Swindon people.

They should take their hats off to a forward-thinking corporation who made Lydiard House public property long before the country's others opened their doors to all-comers.

There has been a house at Lydiard since before the Domesday Book (1086) and it was originally one of many houses owned by Alfred of Marlborough. In the 12th Century the estate passed to the Troisgots family and a corruption of their name gave us Lydiard Tregoze, which is used to distinguish the area around the house from the nearby village of Lydiard Millicent. Lydiard House passed to the Grandison and Beauchamp families until 1420 when it was acquired by Oliver St John. The next owners would be Swindon Corporation, but in the following 500 years, the St Johns produced several interesting characters who helped to give the house its colourful history. Sir John St John (1585-1648) No visit to Lydiard House and Park is complete without a look around St Mary's church, which is tucked behind the house itself. There has been a church here since 1100, though the present structure is 13th Century. So close is the house to the church that it is hardly surprising that for centuries it took on the air of a private chapel to the St John family.

The two most striking monuments in the church both concern Sir John St John and demonstrate how he was struck by personal tragedy throughout his life. His tomb shows him surrounded by the family members whom he mostly outlived, while the statue of the Golden Cavalier underlines the most tragic period of his life. Three of Sir John's sons were killed fighting for the ill-fated Charles I in the Civil War in the 17th Century and the Golden Cavalier - who was originally painted in natural colours but gilded at a later date - is Sir John's son, Edward, who died in battle at Newbury. Ironically, Sir John's sixth son, Walter, was a Puritan and was found to be "backward in kissing the king's hand" when the Stuarts were restored to the throne in 1660. He sat on the family seat at Battersea and used Lydiard as a holiday home. Henry, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke (1678-1751) Walter's grandson, Henry, was born at Lydiard but was another who used the house only occasionally. He became a philosopher and statesman but was disappointed to become Viscount Bolingbroke rather than the Earl of Bolingbroke in 1712. He was even more disappointed when he had to flee to France following his unpopular peace treaties with the French as Minister of War to Queen Anne. His father was forced to obtain the title Viscount St John because the name of Bolingbroke had been tarnished. Henry, however, has been given a kind of immortality as the man on whom Jonathan Swift based the central character in his book, Gulliver's Travels. This political satire, now mostly enjoyed as a children's book, was first published in 1726, three years after Henry received a Royal pardon. Henry's half brother, John, was responsible for the remodelling of Lydiard House. He rebuilt it in 1743 when it took on its current form, complete with the St John arms on the pediment of the front face which bears the inscription "Sanctus in terra beatus in coelo" (Holy on earth, blessed in heaven). The motto hardly seemed to fit John's son, Frederick, who brought a new whiff of scandal to the family. Frederick, 2nd Viscount Bolingbroke (1732-1787)

Frederick never remarried and seemed happier with racehorses. He had a stable of 20 racehorses at Lydiard and was an early patron of George Stubbs. Henry, 5th Viscount Bolingbroke (died 1899) The newly rebuilt Lydiard House enjoyed only a brief heyday and by 1826 the visiting William Cobbett noted an atmosphere of "neglect... if not abandonment" although he said it must once have been a "noble place". The preference of a succession of viscounts for selling the family silver rather than maintaining the property was the chief reason for the decline of Lydiard.

Henry, the 5th Viscount Bolingbroke, did little to enhance the house's reputation. In fact, he will go down in history as the man who objected to the Swindon Railway Works hooter because he thought it would disturb the pheasants nesting on his land. The contrast between Bolingbroke's lifestyle and those of the factory workers, whose lives were controlled by the hooter, meant that there was real resentment of Bolingbroke on the streets of Swindon. There would have been little sympathy for the fact that Henry was having to mortgage Lydiard to pay for his lifestyle and by the time of his death in 1899 it was inevitable that the house would be lost to the Bolingbrokes. The estate was being broken up in the 1920s and in 1943, when Swindon Corporation bought it, it was in desperate need of repair.

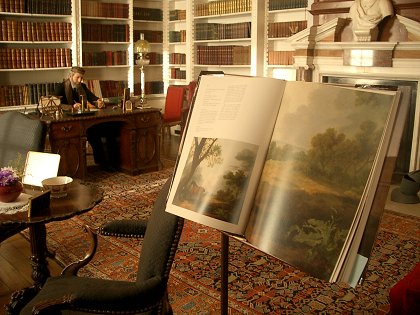

Restoration Swindon Corporation, followed by its successor, The Borough of Thamesdown, and now Swindon Borough Council, have done a magnificent job in rescuing Lydiard House and restoring it to how it looked in previous generations.

When it was purchased it was perhaps a matter of months from being beyond repair but it had been restored sufficiently for it to be opened to the public for the first time in 1955. Since then, a painstaking programme has been undertaken to recover some of the artefacts formerly housed at Lydiard but lost over the years.

It means that today there is plenty to discover at Lydiard House - from its wealth of paintings, to the unique 17th Century stained glass window, to the paintings of Lady Diana Spencer. Best of all, though, is a sense that Lydiard House is enjoying a golden era and looks to be in safe hands. Hopefully the new owners - that is, the people of Swindon - will appreciate it more and preserve it better than some of its previous owners did.

The Walled Garden For the first time in centuries, visitors can now enjoy Lydiard Park's ornamental 18th Century Walled Garden. Opened in May 2007, this ornamental fruit and flower garden has been carefully restored with beds of elegantly displayed flowers, topiary and bedding plants, restored sundial, well, wide pathways and plenty of seats to enjoy the tranquil garden.

The spring flower displaysinclude 18th Century varieties of tulips, hyacinths and crown imperials. Later in the season, summer flowers will include sweet peas, nasturtium and convolvulus. Wall-trained fruit include the rare date-plum and Marie-Louise and Williams pears.

The planting plans for the garden are based on archaeological excavations and expert historical research. Evidence of the type of flowers grown at Lydiard 250 years ago can be found in the beautiful floral illustrations painted on decorative wall panels in the house by the society artist and renowned beauty, Lady Diana Spencer.

Opening Times Lydiard House and Walled Garden are open Tuesday to Sunday 11am to 5pm (Winter closing from November to February at 4pm). Joint admission tickets are purchased from the house, Adult £3.50, Senior £3.00, Child £1.75. Discounts for SwindonCard holders, pre-booked groups of 12 or more people and annual season tickets are available.

There is access for disabled people because rooms open to the public are all on the ground floor. The park, for which there is no entry fee , is open from 7.30am to dusk every day. Also it's free to park your car. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Lydiard House and Park - website | ||||||||

|

|||||||||