Richard Jefferies

Swindon's greatest writer?

Criticised by many but described by others as a prophet or a genius, he was a man with a complex character and an obsessive nature.

He was born at Coate Farm in Swindon on 6 November 1848. His grandfather had bought the farm and a mill and bakery in Swindon in 1800, and it was expected that Richard would carry on the family business. Country life suited him and he developed a deep appreciation of his surroundings. But Richard Jefferies was never going to be satisfied running a farm.

Though certainly not hard, his childhood was tinged with unhappiness. His parents' marriage was less than loving, and there was an uneasiness at home which weighed heavy on Richard's sensitive young mind.

He became a rather isolated child, exploring the countryside alone.

Though apparently confident and unrelenting in his character, he was looked upon by his family as someone with his head in the clouds. As he approached adulthood the farm was falling increasingly into debt, but Richard was more interested in the romance of travelling to Europe than settling down to steady work.

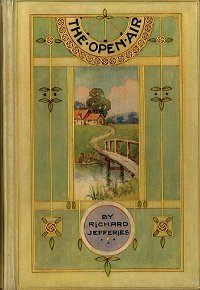

He squandered his money on trips to France and Belgium convinced that his destiny to become a great writer would see him through. His parents were by now losing patience and refused to let him return to the farm. He spent most of his time writing novels and papers but they raised no interest from publishers. Through necessity rather than choice, Jefferies was working as a journalist for the North Wiltshire Herald, but he never wavered from his belief that he would one day achieve some sort of literary immortality. In 1872 The Times published some of his letters on agricultural workers and this lead to regular freelance work writing magazines on country matters. He continued to write novels, but was still waiting for the break he knew would repay the faith he always had in his own abilities. He married Jessie Baden at Chiseldon in 1874 and they moved into a house in Victoria Road, Swindon. In the same year he wrote the novel The Scarlet Shawl but had to pay to have it published and lost money on it. In 1875 this was followed by Restless Human Hearts, but success was still eluding him.

Jefferies was convinced he needed to be close to London to meet his destiny and so moved to Surbiton in 1877.

His novels began to attract some attention and The Gamekeeper at Home, published in 1878, was at last reasonably successful.

Ironically, although he had felt compelled to escape from Wiltshire life, it was his writings about it that were now beginning to build his reputation. The Gamekeeper at Home was centred around the Gamekeeper's Cottage at Hodson and the majority of his books are based on his reminiscences of life at Coate Farm and in the surrounding countryside.

Indeed, much of his writing is semi-autobiographical and draws reference to his early life in Swindon.

Jefferies never lost his appreciation of his home county, but he was now also being influenced by life in Surrey. He was living the kind of idealistic life he had always dreamed of. He regimented his day into set periods of time for writing, reading and walking the countryside - purposefully drawing inspiration from his observations.

And yet all was still not well in his life. He become ill with fistula - a condition affecting the intestines - which caused him some considerable pain. He became agitated and bad tempered and drifted into nervous exhaustion. He was also becoming bored with what he called 'Villadom'. London had served its purpose, but it only intensified his love of the countryside. He was by now an established author, and he felt that he needed to move on. During a holiday, the romance of Brighton captured his imagination and he was drawn to it like a moth to a flame.

He moved to Brighton and was predictably captivated by life in a fashionable town by the sea. But his health was still causing concern. His doctor prescribed a strict diet but Jefferies ignored his advice, believing that the fresh sea air was a cure for anything. It was typical of his outlook on life in general.

He always knew what he wanted, and he always knew what was best. But that was the paradox of Richard Jefferies. He was resolute on one level and yet hopelessly indecisive on another.

Although he hated London, he needed to be near it. Brighton had seemed to be his utopia, but it was too far from the capital. He therefore moved to Kent to try to have the best of both worlds.

He was now comfortably prosperous and enjoyed the freedom of being able to write whatever he pleased regardless of whether it was popular or not. But by now, although he was still only 39, his health was deteriorating. He took a long holiday at Bexhill-on-Sea and then moved to Crowborough on the Sussex Downs but a particularly harsh winter forced the family to the less exposed Goring-on-Sea. Richard Jefferies died there on 14 August 1887 and is buried at Broadwater Cemetery near Worthing. Any consideration of the life and works of Richard Jefferies is bound to invoke controversy. He is the classic example of an author (and a man) whom you either love or hate. He possessed a stubbornness which is difficult to overstate and an incredible intolerance for anything - however trivial - which did not match his exact view of life.

He had an idealistic outlook on life which has been interpreted as naivety by some and an all-consuming passion by others. Some consider the descriptiveness of his writings to be in the league of Thomas Hardy, whilst others can see only a departure from reality.

He seemed to live his life franticly rebounding between carefree appreciation of the wonder of life and the torment of the reality of it and the perceived imperfections of all around him. It is impossible to form an opinion about him until you have read a cross section of his works - and yet that is only likely to add to the difficulty in getting through to the real Richard Jefferies. If Richard Jefferies' intention was simply to persaude his readers to give more consideration to nature and the meaning of life, then Swindon's most famous literary son can rightly claim to have been successful. His work is almost certain to invoke deep thought and lead to strong opinions on the subject. The final irony is that, having been encouraged to think about it, the reader is just as likely to turn hostile to Jefferies' perception of the world as he is to agree with it. |

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Richard Jefferies Society - website | ||||||||

| Richard Jefferies Museum - more details | ||||||||

|

|||||||||